Have you noticed that children seem to always want to push the boundaries? It’s almost as though they are wired to poke and prod us to see how much they can get away with.

Power struggles are an inevitable part of parenting and they start early on. For toddlers, it’s wanting to stay up late, sleep in mummy’s bed, eat ice-cream for breakfast, have daddy feed them – “No Mummy”… “No Daddy” – or wear zero clothing. Actually, for toddlers everything is a power struggle.

For bigger kids it’s almost always wanting more screen time. Or wanting that treat after you said no. For teenagers? How about even more screen time, extended curfews, wanting to drive a car before they’re ready or drinking alcohol before they’re ready (or both).

Research tells us that our children need us to set limits, even though they fight against it like crazy. Kids without limits tend to have lousy outcomes throughout their lives, but it’s a delicate balancing act because kids who have strict limits also often have lousy outcomes. It almost sounds as though you’re damned if you do (have limits) and you’re damned if you don’t.

The truth is that the number of limits our children have is far less important than how those limits are set. When we set limits in lousy ways, we get lousy outcomes regardless of whether there are a few or a lot.

When we set limits in positive ways, we get positive outcomes, and again the number of limits is irrelevant.

It’s not what, it’s how.

My friend, Peter Cook, explained it to his three-year-old daughter, Scarlett, in a way that is perfect for children at any and all ages. I’ve used it with my four-year-old and with my nearly eighteen-year-old.

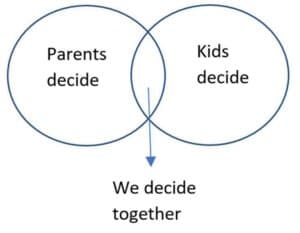

It goes like this: Draw two circles side by side, overlapping slightly. In one of the circles, write the words “Parents decide”. In the other circle, write the words “Kids decide” Explain to your child that there are some decisions that parents make for their kids regardless of what they think. And there are also some decisions that children get to make with no input from parents.

Ask your child to identify some examples of decisions that parents make. Then ask your child to identify decisions that you stay out of.

Next draw an arrow from the overlapping component of the circles. Write “We decide together”. Now explain that some decisions are made by negotiation.

Once you’ve made it clear that you are the parent and you are responsible for certain decisions, power struggles will shift. When there’s a bit of pushback you can smile and say “This is a decision that is in the parent circle”. That’s the end of the story. Sometimes your child will sulk.

There will still be occasional screaming and arguing. But the line has been drawn, the expectation is set and many power struggles will be defused. So long as we don’t abuse the power we have as parents our children can feel secure with us calling the shots we need to call, and either negotiating with – or deferring to – our children for other decisions.

What matters is that when negotiating to do the things they want, they do them in ways you feel good about, and if you don’t feel good, you negotiate until you do feel good. For example; agreeing for your teen to attend a party; they can do so as long as you can personally pick them up at an agreed time.

This may be the toughest and most “advanced” response to power struggles. The more you try and use your power to force an issue, the more you raise the stakes. Teenagers who are trying to form their own identity, separate from us as parents, and want to be seen as independent young adults will naturally push against power, attempting to assert their own.

So, when you start throwing your weight around, via threats, punishments or even rewards, they feel almost compelled to resist us.

How do you avoid making it about power?

Tell them you trust them, you have faith in their ability to make good decisions and you want them to grow to be responsible. Tell them you’re deferring the situation to them, but you’d like them to discuss it with you. Then, instead of rejecting their choices, ask them to help you understand why they’ve made their decisions. Probing, careful questions, combined with logic, patience and love – remove power and allow “adult” conversations around decision making and limits.

There are some power struggles that you might argue are worth fighting. Our teenagers should not be drinking or using drugs. They should not be viewing pornography. They should not be breaking laws.

Depending on the age of your child and what they want to do, “No” might be the only appropriate answer. But even in these circumstances, minimising our emphasis on power and using reason and logic will generally bring out the best results – because these habits emphasise internalisation rather than compliance due to extrinsic contingencies.

There is great irony in our use of power. The more we have to show we have the power to shore up our position, the less power we really have. When our teens are pushing us and we use our power to defend our position, we actually lose power to them. Counter-intuitively our demands for compliance indicate our powerlessness.

We are out of control and we show our desperation to cling to that power by using force. We have the most power when we don’t have to use it, but instead, encourage and empower our children to make decisions for themselves.

One more important point: as your child matures and develops, your circles will overlap more and more. Negotiations will become increasingly common. This is healthy and normal. Then a major shift will occur. The circles will almost entirely separate. And your circle will shrink while theirs enlarges. You will push increasingly large amounts of responsibility onto your child. If we want responsible children, we have to give them responsibility.

Sometimes setting limits with children is like dealing with a helium balloon on a string. They want to shoot off into the sky. They are full of enthusiasm and optimism. They want to dance, and float, and fly, and have fun. That might be in the form of more play time, more junk food, a later curfew or whatever else has them fired up. To be fair, often that’s appropriate.

But we always hold onto that string. Sometimes we bring that balloon nice and close because the conditions are unsafe. Other times we actually hold onto the balloon (like we would if it were floating in the car and getting in the way) so it is completely safe. But to the extent possible, we allow it space to play and dance and delight.