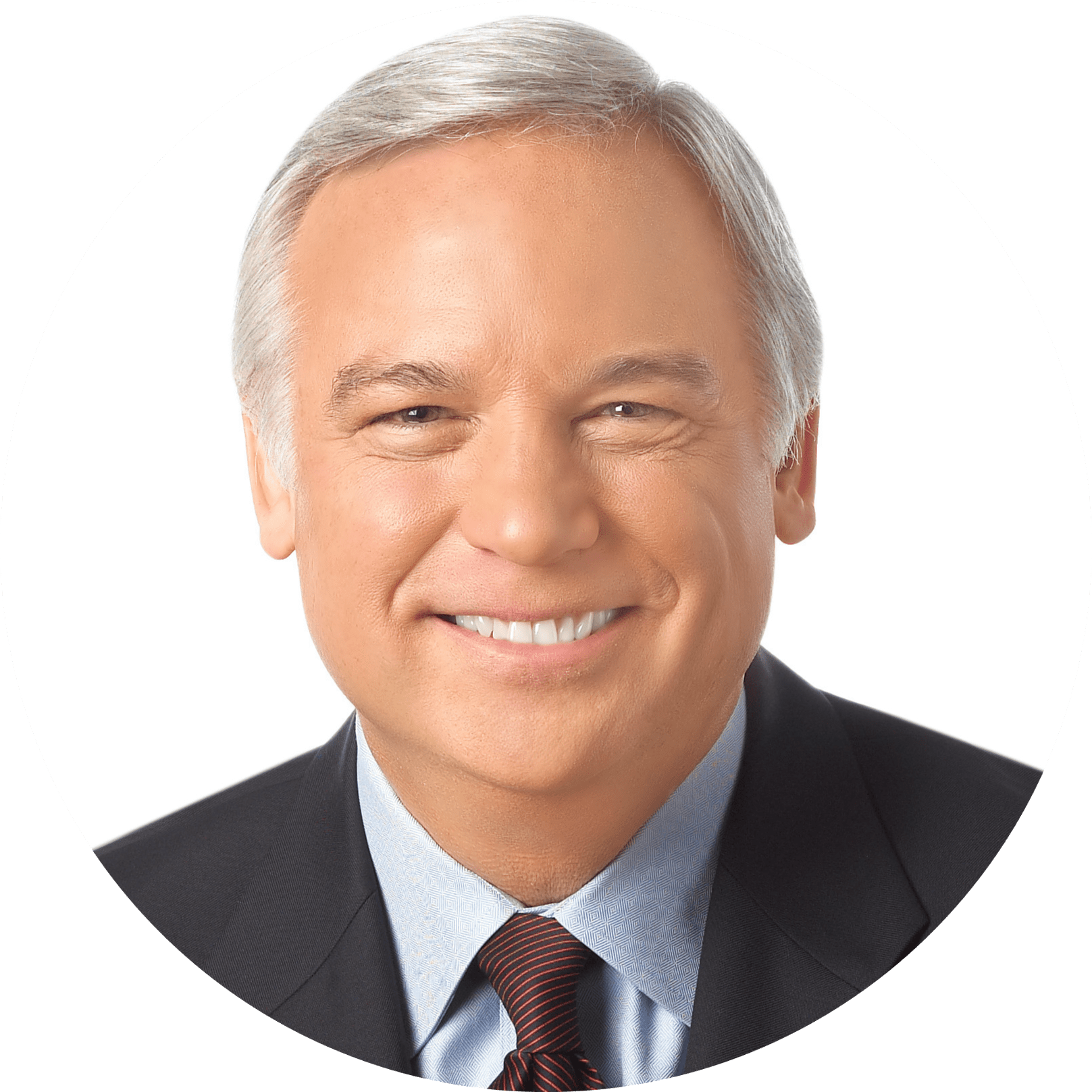

Jack Canfield is a best-selling author, award-winning speaker and an international expert on self-esteem, goal setting, success and life improvement. As the co-creator of the Chicken Soup for the Soul series, he’s taught millions of individuals his formulas for success and has just released ‘I CAN Believe in Myself’ – a children’s book helping children harness the power of ‘I Can’. We were lucky enough to catch up with Jack to find out how we can empower the young people in our lives with this message.

What Were the Motivators Behind Writing ‘I CAN Believe in Myself’?

Firstly, I wanted to reach kids because I always say – if it’s done on time – it’s called ‘education’, if it’s done late – it’s called ‘therapy’. We want to teach our kids high self-esteem, we want to teach them to believe in themselves and to go for their dreams. Too often we don’t see that happening in the schools, so, it’s really up to us as parents and grandparents to do that with our kids.

Secondly, Miriam Laundry – the co-author of the book, wanted to teach her three kids something she had learned in a workshop I ran, based on the exercise called ‘Can’t, Won’t’. In ‘Can’t, Won’t’ you start a series of sentences and statements with “I can’t” that are true for you, for example; “I can’t find time to answer all my emails”, “I can’t lose that last 5 kilos, I can’t stop smoking, I can’t keep my room clean, etc.” Then you go back and say the same things and start the statements with “I won’t” – “I won’t stop smoking, I won’t keep my room clean, I won’t answer all of my emails”. During the exercise people begin to see – ‘WOW, it’s not that I can’t; I’m choosing not to’.

She realised a lecture wasn’t going to get the message across to her kids, so the idea was born to create a children’s book that conveys the same message that ‘can’t is going to stop you – and that there really is no such thing’. You CAN.

How Can We Help Our Kids Turn “I Can’t” into “I Can”?

Establish what’s true. There are ‘I Cant’s’ that you’re telling yourself that aren’t really true, and there are other things you really can’t do – because they are beyond your control – like not being able to go and see your family and friends during the COVID 19 lockdown.

And then ask – ‘Well, what can I do?’ Too often when we’re focusing on the thing we can’t do, we aren’t able to see all the options of what we can do.

A friend of mine lost all of his fingers in a motorcycle accident. He said, “I realised I can’t eat with chopsticks, I can’t play chopsticks on the piano, there’s a lot of things I can’t do… but there’s 10,000 things I still can do. I can talk, I can read, I can sing, I can write poetry” – and he’s now a motivational speaker. We need to help children to shift their focus and attention to what they can do.

There is that old saying – ‘What would you do if you knew you couldn’t fail?’ How much does fear of failure hold us back?

I think fear of failure holds us back a lot, and I think the reason is – most people don’t really understand fear. Fear is imagining the negative outcome you don’t want to have happen.

For example, if there was a snake coming at you – right now, in the present moment – you’re fine. You’d have to imagine the snake biting you, which would happen in the future (it hasn’t happened yet), in order to be afraid of the snake.

So, what we need for kids to focus on is ‘What would you like to have happen?’ They may respond with ‘I’d like the kids to tell me I’m a good athlete, I’d like to do a cartwheel, or I’d like to get an A on my spelling test’ for example. I would then ask them to close their eyes and imagine getting that result – the teachers patting you on the back, the other kids telling you ‘great job’, you’re seeing the ball go through the hoop in basketball or the goal in soccer. In doing that, we use that same function of visualisation to imagine what we want instead of what we don’t want.

One of the great truths of life – is that your body cannot tell the difference between a real event or a vividly imagined event. So, the way to handle fear is to imagine the outcome you want, as opposed to the outcome you don’t want, and then imagine yourself getting it. If you can teach kids to do that and do it yourself as well, you’ll find it’s much easier to take action, and the fear won’t stop you anymore.

When we go into classrooms to read the book and talk to them about overcoming their ‘I can’ts’- we use the example of one of Miriam’s kids who wanted to learn to do a cartwheel. She tried it about five times, fell over and said “I can’t. I can’t do a cartwheel,” and she just walked away.

Miriam then asked her; “Do you really want to do a cart wheel?” She said she did. So, we shared with her the three steps to making it happen;

Number one – you have to choose to believe you can learn to do it, because if someone else can do it you can do it.

Number two – you have to find someone who knows how to do it and ask them to teach you what they know.

Number three – you have to practice.

And that’s true with anything you want to do. It’s an easy three step process – 1, 2, 3 – you can do anything.

What can parents do to help increase their child’s belief in themselves and self-esteem?

Break down what you are asking into chunks. Make it easy, break it down into little steps, set positive expectation (in regards to outcomes), and then celebrate and reward all those steps along the way. Help them experience success one step at a time.

Be Patient. Too often, parents get frustrated and impatient; “Come on you’re not trying,” “You’re not concentrating,” “Let’s go! Focus!” And the kids start feeling like they’re failing, instead of experiencing the process of learning feeling fun. Have you noticed how kids will spend hours learning to play a video game? Why? Because it’s something they really want to do, and nobody is there standing over them, making them feel like they failed. They’re also getting little rewards along the way – winning stars, and points, and coins – the whole thing is gamified to keep them addicted to it. I think we can learn from that.

Believe in the process and your child. When teaching your child to walk. You don’t tell your child “You’ve got 1000 tries, and after that, forget it – I’m not going to work with you anymore.’’ They fall down a lot, they get up, and they fall down, and they just keep doing it – and we keep supporting them until they get it. Adopt the same approach with whatever your child is learning.

Model positive behaviours and attitudes. It’s important to be the kind of human you want them to be and to show them, by example -how. When we model admitting our own mistakes – it helps children realise mistakes are normal and part of the process. When we model sharing our authentic, true feelings – children learn that their feelings are okay. Acknowledging them demonstrates that you, too, are constantly growing and learning. Your children will see you reading, turning off the tv sometimes, challenging yourself, learning new skills. I learned how to juggle when my boys were young, and the balls went everywhere when I dropped them, and they were able to realise that ‘Dad learns new things too, and he doesn’t start out perfectly and so it gives us permission not to do that as well’.

Head to www.pakmag.com.au to tune into our very special 100th episode of the PakMag Parents Podcast with more from Jack Canfield on how to help your young people turn ‘I can’t’ into ‘I can’. For more inspiration from Jack head to www.jackcanfield.com